Sara Vicca (UA, dept. Biologie), Ann Crabbé (UA, dept. Sociologie) and Steven Van Passel (UA, FBE). This blog appeared earlier in Dutch on www.globalchangeecology.blog. Translated by Jonas Lembrechts with DeepL.

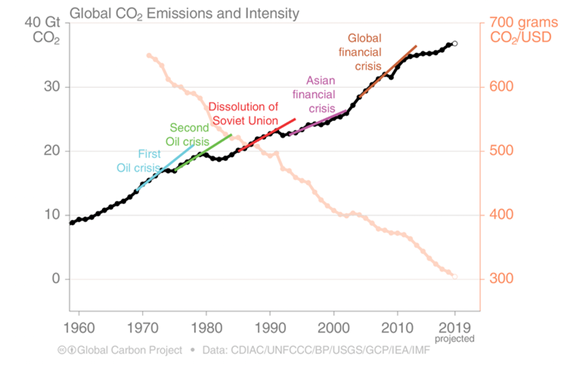

Is the coronavirus good news for the climate? It’s a recurring question these days. Not incomprehensible, because the impact of the measures on our emissions is clearly noticeable. Car traffic and energy consumption are decreasing and in the meantime it has been calculated that CO2 emissions in China decreased by a quarter in February. But these decreases are limited in time. In China, emissions are already rising and history teaches us that a decrease in CO2 emissions due to a crisis is usually short-lived. Emissions also fell during the oil crisis in the 1970s and during the banking crisis in 2008-2009, but after the crisis emissions rose again each time to break new emission records.

Will it be the same this time, too? Will CO2 emissions rise rapidly again after the corona crisis until the end of the year up till the level from before the crisis? Let’s hope not. Governments and all those who (rightly) take measures to re-launch the economy after the crisis, hopefully opt for measures that contribute to a ‘sustainable’ relaunch of the economy. This crisis may be an opportunity to take further steps on the transition path that some people have chosen very deliberately before.

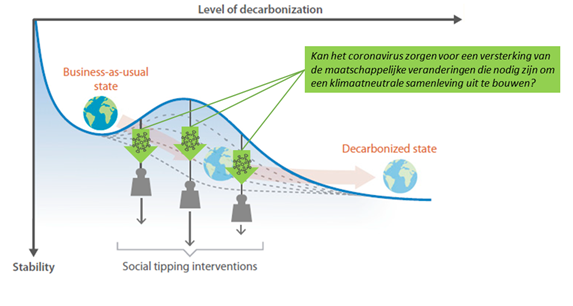

Which aspects are most important here? What should we, as a society, do to turn the corona crisis into a turning point in greenhouse gas emissions? A recent study on social tipping dynamics offers more insight into this. In February of this year, a group of scientists (including some big names such as Johan Rockström and Hans Joachim Schellnhuber) published a study in which they discuss so-called social tipping interventions (STIs)[1]. These are social and technological changes that, through a snowball effect, can greatly accelerate the necessary social transition to a climate-neutral society. These social tipping interventions concern the following social aspects: (1) energy production and storage, (2) human settlement, (3) financial markets, (4) norms and values system, (5) education system, and (6) information feedback. Below we briefly summarise what the study indicated and discuss some possibilities in the light of climate action in the (post-)corona era.

- Energy production and storage

The energy transition takes a central stand in tackling the issue of climate change: fossil fuels must be used in such a way that be replaced by renewable energy sources as soon as possible. The most important factor influencing the switch to fossil-free energy production is the financial return of the sustainable alternatives. The experts indicate that the tipping point here is likely to be reached when fossil fuel energy production becomes more expensive than the alternatives. Data shows that we are on the verge of reaching this critical threshold; renewable energy prices have fallen sharply in recent years and in many regions renewable energy has already become the cheapest energy source.

However, significant investments are still needed to adapt the existing electricity system to renewable sources such as wind and solar. An important action point of STI put forward here is the reorientation of fossil fuel subsidies towards subsidies for a decentralised energy system with the necessary energy storage and supply and demand support services to meet the demands of non-dispatchable, volatile renewable energy sources like wind and solar (smart grid and smart appliances).

The above insights can serve as a guide for the economic stimulus packages that will follow the corona crisis. The boss of the International Energy Agency, for example, has already called for the stimulus packages to reduce the flow of money to fossil fuels and to make full use of sustainable investments that will accelerate the energy transition and, moreover, create many green jobs. Additionally, Jos Delbeke (former Director-General of the EU DG Climate) and Johan Albrecht (Itinera and environmental economics professor at UGent), among others, indicated that support measures for the badly affected airlines should be linked to sustainability measures such as an aircraft tax and kerosene tax.

- Human settlement

Our homes and buildings account for about 20% of global CO2 emissions through direct and indirect emissions and reducing these emissions is a significant challenge for the transition to a climate-neutral society. An example of an STI here are large-scale demonstration projects such as carbon neutral cities. Such projects are important as a source of information and inspiration for the general public, and as a stimulus for the development of sustainable building materials and technologies.

One of the plans in the Green Deal for Europe is a so-called renovation wave, which will aim for 3% renovation per year (instead of the current 1%). This will require technological, organisational, social and financial innovation . In addition to climate and health benefits, the renovation wave can also offer many opportunities for economic growth and job creation. At the moment, however, it is still unclear to what extent the corona crisis will lead to delayed implementation of the European Green Deal, or rather a flywheel effect: the economic stimulus packages can also go hand in hand with the implementation of the Green Deal and mutually reinforce each other.

- Financial markets

The 2008-2009 financial and economic crisis showed how quickly an event in one sector (the banking sector) can destabilize society and bring about changes in individual investment and consumption behaviour as well as in policy actions. In order to limit global warming to well below 2°C (as agreed in Paris), 33% of oil, 49% of gas and 82% of coal reserves should not be burned. This suggests a risk of a so-called carbon bubble, which means that investments in fossil fuels will be insufficient if we comply with the Paris Climate Agreement.

A growing number of analysts believe that such a financial carbon bubble is emerging and that it could burst if a critical group of investors see it and act upon it. Simulations show that only 9% of investors can already tip the system. Other investors would then quickly follow. An example of an STI that could play an important role here is the divestment movement, where money is desinvested from fossil fuels, and instead invested in sustainable projects: “divest from what harms, invest in what helps”. A snowball effect could be caused when banks and insurance companies would warn about this carbon bubble. These concerns are already growing in Europe, and according to the study, the reduction in financial and insurance support for coal projects could indicate that a tipping point is near.

The corona crisis also shows how an event can disrupt the financial markets. On 12 March 2020, the Brussels stock market index Bel20 experienced its biggest fall ever (-14.21%), since the start of the index in 1991. Investors are uncertain about the economic impact of the coronavirus. Arrangements have been drawn up for deferring payment of loans for both companies and private individuals, in addition to, among other things, guarantee schemes, annoyance premiums and deferral of payment. In the longer term, it is very unclear whether the corona crisis will strengthen the carbon bubble or just slow it down. An important recommendation is that the recommendations of the TCFD (Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures) is followed thoroughly in order to avoid exactly that carbon bubble.

- Norms and values system

The extraction and use of fossil fuels out of line with the Paris Climate Agreement targets is arguably immoral, as it would cause widespread grave and unnecessary harm. Moreover, we know that the most vulnerable social groups are disproportionately affected by climate change. And then there is intergenerational inequality: future generations will be hardest hit, while they have no voice in the debate today.

Fortunately, norms and values can change. Global climate protests and the school strikes for climate may be an indication that such a change in norms and values is taking place. A recent study showed that a dedicated minority of about 25% of a group can change the opinion of the majority and thus change established norms and values. If dominant norms and values in society change, the pressure on policymakers to change existing institutions (regulatory systems) will increase. Also policy initiatives such as the European Green Deal are an important incentive to change the behaviour of companies, among others, a self-reinforcing process of change can be set in motion, in favour of climate neutrality.

Perhaps the corona crisis may lead to a shift in dominant values and norms in society. While many are concerned about the economic impact of the corona measures, others underline the extent to which the stagnation of social and economic life offers room to live differently, with less consumption pressure, more time for what counts (the family) and with the mental relief of being able to step out of the ‘rat race’ for a while. Political scientists are waiting, but anticipate shifts in dominant political values: more willingness to invest in ‘soft sectors’ (such as the health sector), more room for solidarity, while denouncing globalisation and dependence on international markets. The latter may give rise to the strengthening of solidarity within Europe, including in the joint development of a greener economy that is less dependent on ‘external’ fossil fuels.

- Education system

General knowledge about the causes, consequences, and solutions of climate change has often been lacking, and this knowledge gap is often at least one of the reasons why people do not feel addressed or involved in the climate story. On the other hand, the recent school strikes show that younger generations are waking up to the climate problem. It is estimated that the number of school strikers grew to 1.5 million pupils in 125 countries in six months’ time. Many educational initiatives have now been set up to inform pupils and other target groups about climate change. Quality education not only supports and strengthens climate knowledge, but can also inspire climate action and changes in individual and collective behaviour.

The big challenge, during the corona crisis and afterwards, is to reduce school and learning delays among pupils and students. Specialists are already worried about the proportionally greater learning disadvantages that vulnerable pupils are suffering as a result of the prolonged school closures. Digital distance learning may work for children who live in wealthy families, but it does not offer a fully-fledged alternative for everyone.

- Information feedback

If we want to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we need to know where the emissions come from, which products cause more/less emissions, and how to make sustainable choices. Such information can be provided to consumers, for example through product labelling programmes. On the other hand, the population also needs to be clearly informed about the purpose and impact of certain measures, such as shifts in subsidies and taxes. Sufficient communication about the impact of individual choices on emissions can encourage societal changes, although we know that knowledge alone will not suffice.

In these Corona times, Belgium excels in informing the population objectively, correctly and serenely. We were even praised for this by the British newspaper The Financial Times. Every day, experts give an update on the state of affairs: number of infections, hospital admissions, intensive care units, the number of people who could leave the hospital and the death toll. These moments of information are also used to comment on to counter rumours, misunderstandings and attempts to evade lockdown.

Perhaps this crisis communication can serve as a source of inspiration for sharing information about the climate problem? Inform people objectively and calmly about what works and what doesn’t, what has already been achieved and what is still ahead of us. Such transparent communication strengthens the collaborative spirit needed to transition to a climate-neutral world. Inform the public that the climate transition will not only cost money, but will also bring financial benefits and that we will strive for a more pleasant and liveable world.

In conclusion. Rockström, Schellnhuber and their co-authors also point out the importance of institutional changes in their article. Government subsidies and tax systems need to be reformed in order to stabilise the emerging more sustainable system. Without the necessary adjustments concerning financing, taxation and regulation, the transition might become increasingly unstable, bouncing back and forth between the old and new social order, delaying the transformation. The authors of the study indicate that extreme climate-related events, such as extreme heat waves and floods, might act as a ‘window of opportunity’ to make such adjustments. The corona crisis can also lead to reforms, including in financial flows and regulations. When that happens, let’s take advantage of that opportunity to, in one fell swoop, also tackle the climate problem.

[1] Ilona M. Otto, Jonathan F. Donges, Roger Cremades, Avit Bhowmik, Richard J. Hewitt, Wolfgang Lucht, Johan Rockström, Franziska Allerberger, Mark McCaffrey, Sylvanus S. P. Doe, Alex Lenferna, Nerea Morán, Detlef P. van Vuuren, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber. Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Feb 2020, 117 (5) 2354-2365. https://www.pnas.org/content/117/5/2354